The art of the snapshot photograph

A snapshot is is often used to describe a photograph in a somewhat derogatory sense. A photo that was taken quickly, with little regard to the composition, framing, and camera settings. A photo that was taken without much thought.

However, when a photo is described as a snapshot, that does not necessarily mean it is a bad photo. There have been (and still are) many popular and award-winning photographers who make use of the snapshot style, such as Gary Winogrand, William Klein, Nan Goldin, and William Eggleston, to give a few examples.

In this article we'll look at the snapshot in more detail, covering a brief history, and exploring how technical imperfections can add to rather than detract from the photograph's aesthetic.

History of the Snapshot

In the early days of photography, taking a photo was quite a complicated affair. Cameras were big and heavy, you required technical knowledge to correctly operate the camera, and you would need a darkroom to create actual prints of the photos you could see.

This changed with the introduction of the Kodak Camera in 1888. This was a simple, uncomplicated box camera that came pre-loaded with film for 100 photos. When you'd used up the film, you sent the camera back to Kodak to have the film developed.

But the real revolution in bringing photography to the masses was the Kodak Brownie camera, introduced in 1900. This camera allowed reusable film, but most importantly it was available for a low cost ($1) that made it accessible to most families.

1913 in Bayport by an iconoclast on Flickr (licensed CC-BY)

The Brownie was marketed as being so easy to use that even a child could use it. It had a simple fixed focus lens, a single shutter speed, and used narrow apertures to create a deep depth of field that put most of the frame in focus.

The first models didn't even have a viewfinder. You relied on V shaped sighting lines on top to try and aim the camera at your subject correctly. Later models did add viewfinders, but these are very small and not particularly accurate, nothing like the through-the-lens viewfinders / screens we are used to having today.

Kodak Brownie 2 Box camera by Håkan Svensson on Wikipedia (licensed CC-BY)

As you can imagine, these limitations meant that it was not really possible to create a carefully composed photo. Most would be shot with the subject in the center as far as possible, to avoid cutting parts off at the edges of the frame.

Tea with friends, and one must wear one's finest hat! by James Morley on Flickr (licensed public domain)

While the access to a cheap camera meant that people could better record special events in their lives, one of the main differences the Brownie brought with it was the photography of everyday life. Prior to the Brownie a person was unlikely to have a camera, and extremely unlikely to employ a photographer just to photograph the banalities of life. But with a cheap camera and film this became more common.

The Brownie was really the camera that brought the snapshot photo into common usage.

Within a couple of years of the Brownie's release, the Pictorialist movement started to gain greater strength. While not explicitly aimed against snapshots, the Pictorialists aimed to put the emphasis in photography on artistic expression rather than simply just photographing a scene / subject as it appears to the eye.

Through their efforts, the Pictorialists managed to have photography recognised as art - the equal of painting and sculpture. Snapshots, of course, typically lacked any purposeful artistic expression. While you could find galleries showing photographs, it was very unlikely any of those photographs would have been snapshots.

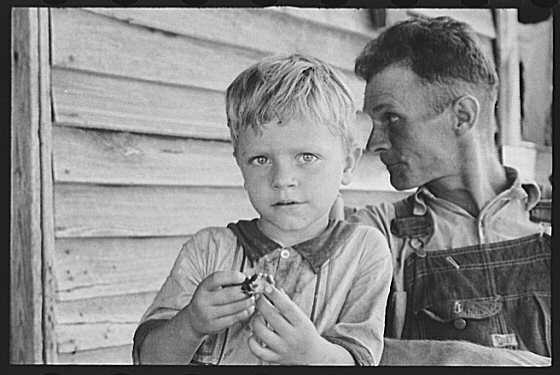

In the 1930s started a small backlash against this way of thinking. Walker Evans is often thought of as being the father of documentary photography. He photographed scenes and people in the rural south of the US, capturing them in a documentary style, rather than an artistic interpretation.

Charles Burroughs and Floyd Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama by Walker Evans (licensed public domain)

While Evans' work and the documentary style of photography may not be quite the same thing as what most think of as snapshot photography, the main thought behind both is the same. The goal of the snapshot is to record a moment in time, the aesthetics of the photo are secondary. While the goal of the art photographer is an aesthetically pleasing photograph - the subject is secondary.

It was John Szarkowski, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who really brought snapshots into the realm of art. In his 1966 exhibition and book The Photographer's Eye, Szarkowski included photographs by well known photographers and studio portraits, alongside newspaper images and snapshots.

In his introduction from the exhibition's catalog, Szarkowski argues that the art of photography is to reveal that which already exists (The Thing itself

). He goes on to say, in his second argument The Detail

:

The photographer was tied to the facts of things, and it was his problem to force the facts to tell the truth. He could not, outside the studio, pose the truth, he could only record it as he found it, and it was found in nature in a fragmented and unexplained form—not as a story, but as scattered and suggestive clues. The photographer could not assemble these clues into a coherent narrative, he could only isolate the fragment, document it, and by so doing claim for it some special significance, a meaning which went beyond simple description. The compelling clarity with which a photograph recorded the trivial suggested that the subject had never before been properly seen, that it was in fact perhaps not trivial, but filled with undiscovered meaning. If photographs could not be read as stories, they could be read as symbols.

In the 1960s, street photography started to become more popular, Garry Winogrand's photos of everyday life in New York particularly standing out. These photos captured life as it happened, photos that were sometimes tilted, taken quickly, effectively snapshots.

More recently we have a massive increase in snapshot photography thanks to the inclusion of a camera built into every smartphone. Just as the Kodak Brownie revolutionized photography in the early 20th century, so the phone camera has revolutionized photography in the early 21st century.

That's why I'm easy… Easy like a Saturday afternoon. ☀️🌳♥️ #hammock #relax #swing #nature #peace #calm #beautiful #sky #trees #birds #photooftheday #iphone #weekend by Jen Knoedl on Flickr (licensed CC-BY)

People are again empowered to take snapshots of the everyday, and like the Brownie there is often little control over the resulting images. And for most people no control over the image is wanted.

Another modern phenomenon is found photos

, that is everyday snapshots taken by others. Old photo albums, boxes of slides, and packets of old prints sold off cheaply at yard sales are bought up by curators of photography.

Creepy little boy holds his cat in front of a mirror by simpleinsomnia on Flickr (licensed CC-BY)

The images are then displayed, be it in an exhibition or online on a blog, often with no link between one image and the next. These images, with no explanation as to why they were taken often have a certain charm. Without the context, the viewer is left to try and put their own interpretation on the meaning behind the photograph.

FOUND: Surprise by delunula dot com on Flickr (licensed CC-BY)

The Snapshot as an art form

Non-snapshot photography is based around the careful formation of an image. Choosing a focal length, framing, composition, depth of field, and shutter speed to create a picture that shows what you want to highlight about a subject, while eliminating or at least reducing what you don't want to show. Photos are often planned and some can take a lot of work to bring about.

Non-snapshot photography is often based around capturing the less ordinary. Subjects such as beautiful landscapes and beautiful people.

Snapshot photography is the opposite. Subjects are the mundane and everyday, or the sides of life people would rather ignore than have shown to them. There is no direction of the scene or the subject, it is a spontaneous capture.

Man and fish, Staten Island Ferry Terminal by Ryan Vaarsi on Flickr (licensed CC-BY)

The images often eschew the 'rules' of photography. Often the subject will be centered. All of the image, including extraneous elements will be in sharp focus. When flash is used, it is unflattering direct flash, from the same position as the camera.

Matthias by mcvickerphotog on Flickr (licensed CC-BY-ND)

Often there can be items in the frame the photographer did not intend to include in the photo. The photo may be badly processed or damaged if taken on film, or could have been processed in a certain way if digital.

The goal of snapshot photography, from the point of view of the photographer at least, is to show life as it really is, rather than a 'constructed' representation. Of course, there is still manipulation here - the photographer still chooses where to point the camera and at what point to press the shutter. But artistic intention is not the driver behind the photo, just the goal to record what was seen.

Snapshot, Taipei, Taiwan, 隨拍, 台北, 台灣 by bryan... on Flickr (licensed CC-BY-SA)

A difficult question arises when we look at what makes a snapshot photo into art. When taking a photo ourselves, we understand the context behind that image. But if it is the combined lack of artistic intent and lack of context that transform a photo from snapshot into art, then how can we determine if our own snapshots are art?

I would say this is partially possible, but it does depend on the subject. Taking street photography as a good example, you can take a photo of someone or some scene you find interesting. While you do have some context to the photo, all that context will be is that you saw the person. You don't know them, you don't know where they're from, or where they were going. All you know is you saw them and took a photo. This provides a good lack of context for judging the aesthetics of the image on its own merit.

Street_Chemnitz_150111_005.jpg by Dirk Förster on Flickr (licensed CC-BY)

You can, of course, also take photos in a snapshot style without the photos technically being snapshots. In the 1990s a snapshot style was very popular for fashion photography, often using direct on-camera flash. Yet models were used, they were directed by the photographer, and there was certainly artistic intention behind the images.

One reason why a snapshot style of photography may be used it because it seems more raw, more real. We're seeing a similar thing at some photo stock libraries now - they are saying that clients want more photos of real people doing real things, rather than staged obvious 'stock' photos. They want stock photos that don't look like stock photos. And where before they had strict criteria for submissions in terms of image quality, they are now clamouring for shots taken with phones.

To conclude this article, I'm not saying that you should completely forget all the guidelines and technical details of photography and start blindly taking photos of anything that interests you in full auto mode. But rather, we shouldn't dismiss snapshots as merely the work of uninformed amateurs. It is precisely because they are the work (or at least appear to be the work) of uninformed amateurs that allows some snapshots to take on a new context and be considered as art.